The study investigated how creative practice and co-design methods could be used to support the dissemination of positively deviant strategies for improving quality and evidence about newly characterised best practice within elderly patient medical wards. The research was funded through the Evidence Based Transformation Theme of the NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) CLAHRC (Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health research and Care) YH (Yorkshire and Humber) and is supported by the Translating Knowledge into Action (TK2A) theme

Funded by: CLAHRC NIHR YH

Partners: University of Leeds

Team: Paul Chamberlain, Claire Craig, Anne Marie Moore, Sarah Smizz

Positive deviance is an asset-based, bottom-up approach to behavioural and social change within communities. It draws on individual and community strengths and pre-existing resources considered positively deviant (Tuhus- Dubrow, 2009, Sternin and Choo, R., 2000; and Singhal et al., 2010).

The approach assumes that problems can be overcome using solutions that already exist within communities. Despite facing the same constraints as others, ‘positive deviants’ identify solutions and succeed by demonstrating uncommon or different behaviours (Baxter et al 2016 p.2).

This approach holds much promise and attention has turned to how it might be applied within health service contexts.

If the potential of the positive deviance approach within healthcare is to be realized it is necessary to find ways to identify positive deviant wards, cultures and individuals within complex and ever-changing systems and create mechanisms to communicate what these are to create the potential for their implementation.

Baxter et al. (2015) examined whether a positive deviance approach could be used to identify ward teams that were performing exceptionally well on patient safety and explored strategies for achieving success.

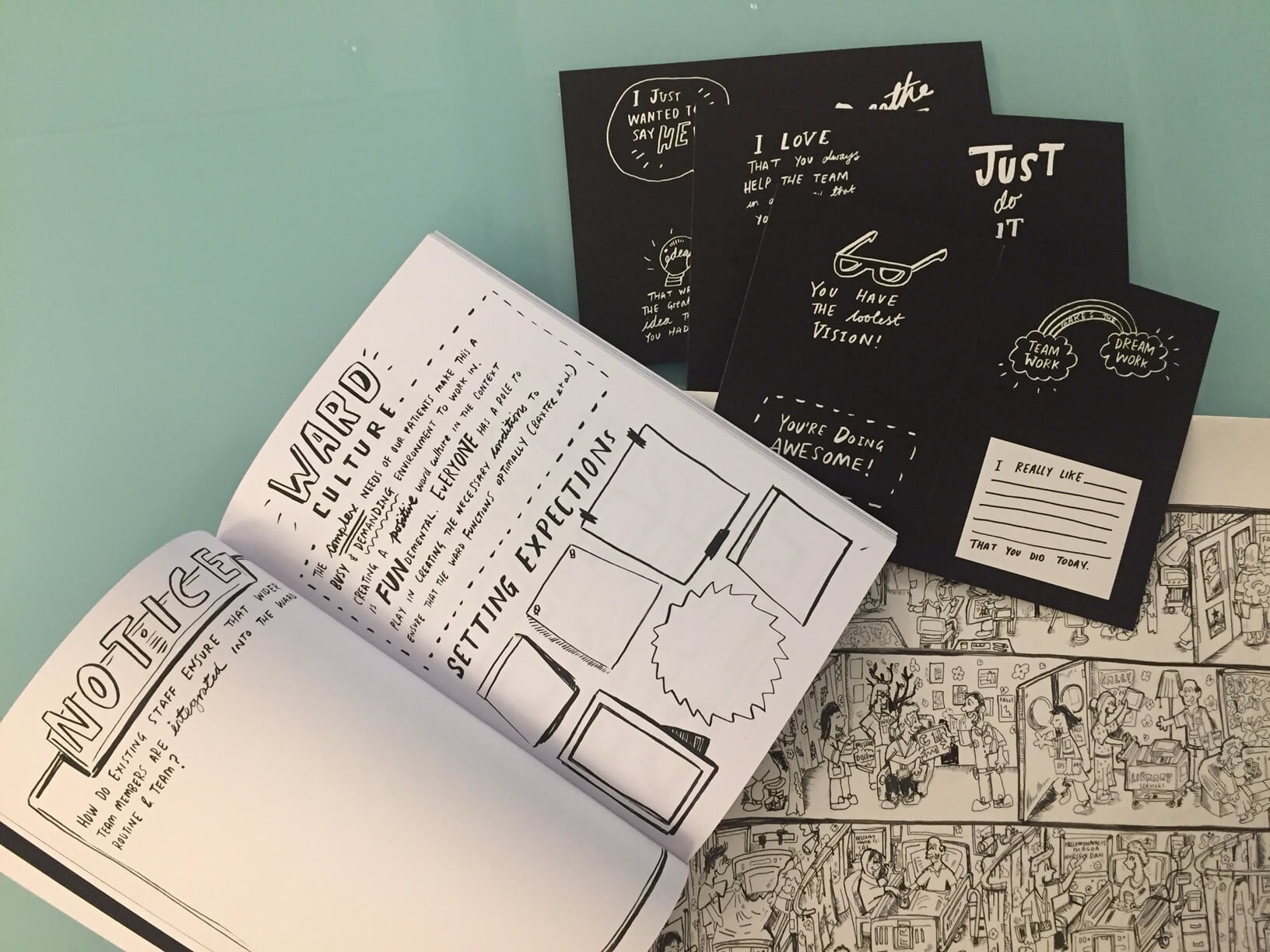

Hypotheses about strategies, behaviours, team cultures and dynamics that facilitated the delivery of safe patient care were generated and 14 key themes representative of positively deviant elderly patient medical wards were identified. These were; Knowing Each Other, Trust, A Multidisciplinary Approach, Integrated Ward Based AHPs, Working Together, Feeling Able to Ask Questions or for Help, Setting Expectations, It’s a Pleasure to Come to Work, Learning from Incidents, Acquiring Additional Staff, Stable and Static Teams, Focus on Discharge, Directorate Support, and Keeping Patients and Relatives Informed.

Baxter’s study raises interesting research questions, particularly in relation to dissemination and adoption of findings. If the strength of the positive deviance approach is its focus on community engagement and involvement, seeing solutions located within existing resources, how is it possible to translate these findings to other communities/settings/wards which have not been involved in the process? If solutions are internally generated rather than externally imposed how can they be regarded as feasible within the resources of other contexts? What are the implications of this in relation to dissemination and knowledge mobilization?

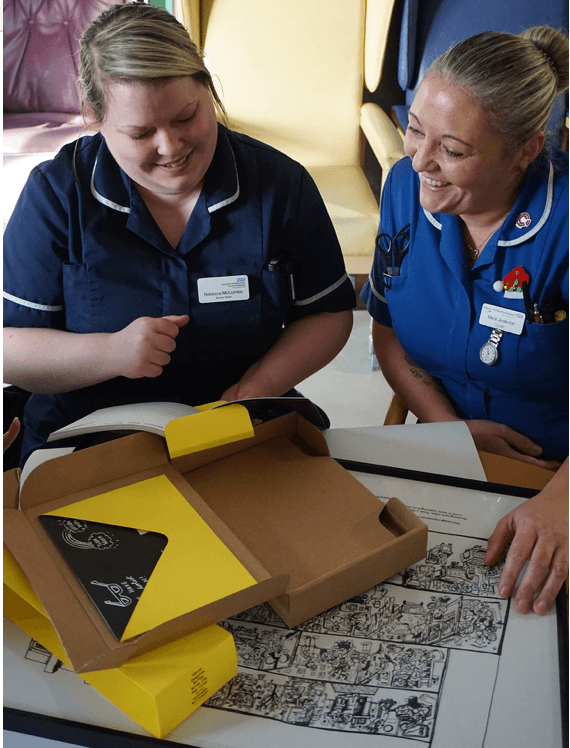

Co-design workshops were undertaken with participants recruited from a local ward team (site 1). The research team used findings from the co-design workshops to develop a set of interventions and artefact installations designed to embody some of the positively deviant strategies and characteristics.

The project involved the intervention and installation of the co-created artefacts into sites 1 and 2 (not involved in the co-design):

The study research questions were as follows:

1) Can creative co-design help ward teams to disseminate positively deviant strategies?

2) Does using creative practice and co-design methods to support the dissemination of positively deviant strategies have an impact on the ward?

3) What is the experience of being involved in this process for staff on the units?

4) Is there a difference in the experience and impact of the critical artefacts between wards engaged in creative practice and co-design of creative interventions and those that were not?

5) Which types of creative co-design methods work well in this context?

‘The books have gone down a treat with established members of the team as well as new starters’..

Evaluation post-installation showed that participants found the co-design workshops ‘enjoyable and thought provoking’. The co-creation of interventions to prompt conversation was successful and staff spoke of how this had offered an opportunity for reflection and discussion relating to the positive deviant strategies. Future studies could explore longer term strategies for evaluation to determine whether the interventions supported extensive dissemination of the themes and whether this dissemination of the positive deviant strategies have a measurable and lasting impact on the ward.

to top

to top